The Murderers and Smugglers of Old Rye

With its half-timbered houses and cobbled streets, Rye is as quintessentially English as they come.

But look below the surface, and you’ll find tales of smugglers, invasions, and murders.

As you walk up the cobbled streets to the town’s churchyard, you cannot avoid the history. You pass a pub, the historic Mermaid Inn, that was re-built in 1420! And the church itself, St Mary’s, has a turret clock that claims to be the oldest working clock in the country. If you climb the clock tower, you can often see as far south as the power station at Dungeness, and across to the cliffs by Pett Level to the west.

In medieval times, the threat of invasion from France led to the formation of the Cinque Ports – a confederation of Channel ports which formed a key part of southern England’s coastal defence, and which included Rye. The arrangement thrived in the Middle Ages but became less important due to the professionalisation of the navy and the shifting coastline, which left Rye and several of the ports inland.

The smugglers

The town looks over Romney Marsh, which is a large, flat, low-lying, and almost empty area with several isolated churches. The marshes were often regarded as a weak point in the event of an invasion and a paradise for smugglers.

Smuggling began in the Middle Ages when wool, the backbone of the medieval English economy, was smuggled out to continental Europe. The smugglers were known as ‘owlers’ due to the owl-like noises they used to communicate at night. But by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, high import duties on products like alcohol, tobacco, lace, and tea made it more profitable smuggling goods into the country, and customs officers struggled to control Romney Marsh.

Being located close to the marsh, Rye was a smugglers’ town where magistrates and revenue men struggled to keep things under control. The smugglers were violent men, notorious for killing officers and anyone who took an interest in their affairs, which meant many ordinary people turned a blind eye to their activities. In fact, some of the locals were grateful for the smugglers, who could supply products like tea at a lower price.

The infamous Hawkhurst Gang from the village of the same name were regular customers at the Mermaid Inn. And when they drank there, they’d sit with their weapons on the tables, clearly with no fear of the authorities. But their downfall came in 1747 following a successful raid in Dorset where a consignment of tea had been seized. A reward was issued, and despite the gang’s intimidating reputation, someone stepped forward with damning evidence. Both the witness and the officer sent to protect him were tortured and killed by seven of the smugglers, and the sheer brutality of this act turned many people against them. All seven were arrested, tried, and found guilty of murder. More gang members were arrested for the raid, and those still at large turned on each other.

Smuggling continued until the early nineteenth century, when war with France led to new coastal defences around Romney Marsh. The invasion never came, but these defences and the increased military presence in the area served as a significant deterrent to smuggling, which went on to face further threats from the formation of HM Coastguard before being rendered economically unviable in the mid-nineteenth century when the government slashed import taxes.

The tales of smuggling on Romney Marsh have provided a source of literary inspiration. Rudyard Kipling, who lived in Sussex for over thirty years, wrote the poem ‘A Smuggler’s Song’, you can find painted onto a wall of the Mermaid Inn. At around the same time, Rye-based author Russell Thorndike created Doctor Syn, a mild-mannered vicar of a Romney Marsh parish by day, ruthless smuggler leader by night and protagonist of a series of novels.

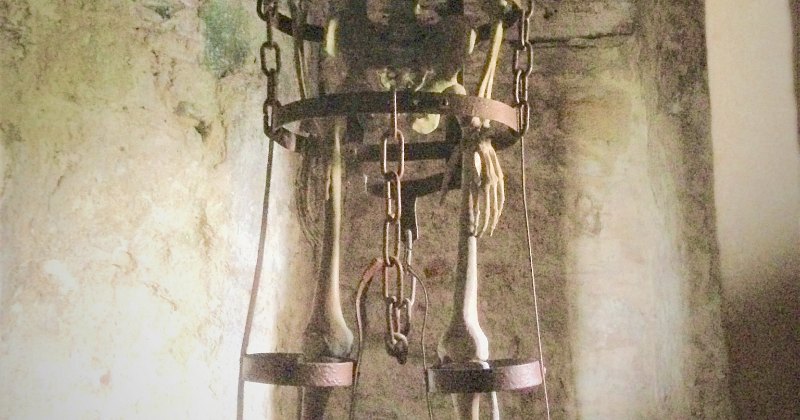

If you’re visiting Rye, the castle, known as the Ypres (pronounced ‘wipers’) Tower, is worth a visit for to find out more about the history of this fascinating place. You can see artefacts from throughout Rye’s history, such as a smuggler’s signalling lantern, as well as a map which shows you the lie of the land and the defences that were installed to guard against invasion. More macabre is the full-size replica human skeleton encased in a gibbet, the metal cage that dead criminals were encased in after being hanged. These were displayed at crossroads to warn people of the consequences of breaking the law.

The mistaken murder

Another of Rye’s famous tales is the notorious ‘murder by mistake’ which happened in 1742. It started when a butcher, John Breads, swore revenge against the mayor, James Lamb, who had fined him for selling meat for more than it was worth. So, Breads decided to take revenge. And he got his opportunity on the night of 17th March 1742. That night, there was a banquet on board a ship docked in the harbour, and Lamb had been invited. Breads knew this, and he also knew that to get back from the harbour to his house, Lamb would have to walk through the churchyard. He waited there, knife in hand, reckoning that in the moonlight, he should be able to spot the mayor in his distinctive red cloak.

Unbeknown to Breads, Lamb was ill at home. He’d sent his brother-in-law, Alan Grebell, with his red mayoral cloak to show he was going as the mayor’s representative. Grebell had a lot to drink at the banquet (French brandy, presumably smuggled, had been served), and it was he, not Lamb, who was attacked and stabbed by Breads as he staggered through the churchyard. Breads immediately fled, and Grebell didn’t even realise he’d been stabbed, he just went home and decided to sit by the fire for a while before going to bed. He was dead by the next morning. Breads, whose blood-spattered knife was found in the churchyard, was quickly arrested and imprisoned in the Ypres Tower. He was tried for murder two months later. The trial is unique in English legal history because it’s the only murder trial in which the judge, Lamb, had been the intended victim. The verdict was never in doubt; they found Breads guilty and sentenced him to death.

This story certainly raises a few questions: why, for example, did Lamb officiate at the trial? Even in the eighteenth century, judges were supposed to be impartial. If you ask around in Rye, you might hear a different take on this fatal case of mistaken identity, and it concerns the Hawkhurst Gang!

The ‘unofficial’ version is that Lamb was in their pocket, but Grebell knew this and was planning to expose the mayor’s corruption. Somehow, Lamb knew that his brother-in-law knew and so had him killed, using Breads as a convenient fall-guy. This too raises a few questions; perhaps they should be considered over a drink in the Mermaid Inn!

What’s in no doubt is that the hanging of John Breads took place out on the marsh, and afterwards his body was enclosed in a gibbet and left there. Gradually, over the next few decades, his bones were stolen. When only the skull was left, it was taken to Rye Town Hall where it remains to this day. There are apparently plenty of requests to see it, although the council always refuses these because displaying actual human remains wouldn’t be appropriate. Surely the fake skeleton in the Ypres Tower is gruesome enough?

As well as being a Driver-Guide on Rabbie’s tours operating out of London, Nick is also a writer and a former history teacher. He is a regular blogger at http://nick-young.blogspot.co.uk.